We live in an era of endless digital entertainment. Every week brings a new TV show, album, movie, game, or podcast to cure our boredom. Advertisers create urgency and FOMO in our daily lives. People now take pride in the number of Netflix shows they’ve watched, and if you haven’t seen the latest Game of Thrones episode, everyone cries shame. In fact, if you aren’t currently watching something, you’re labeled an outcast. Novelty drives these million-dollar industries, promising status and dopamine. However, when it comes to long-term satisfaction and happiness, variety is not the spice of life.

The Problem with Constant Digital Novelty

In the book Stumbling On Happiness, Harvard psychologist Daniel Gilbert explains why variety can make people less happy. Imagine eating steak at a fancy restaurant when suddenly the chef offers you a special gift. On the first Monday of every month for the next year, you get to enjoy a free meal. To ensure enough ingredients, the chef asks what meals you would like beforehand. You already know that you love their steak, but ordering the same meal twelve times could get boring, and what if the other dishes are better? Therefore, you tell the chef you would like the steak dinner every other month, filling the remaining visits with pasta, lobster, and chicken. This reasonable decision would actually be a mistake.

Research on Variety and Happiness

Researchers conducted an experiment similar to this scenario. They invited participants to eat a snack once a week for several weeks. Each participant was assigned to one of two groups: the non-variety group and the variety group. Participants in the non-variety group ate their favorite snack every week. Participants in the variety group ate their favorite snack on most visits and their second favorite snack on others. The study measured the participants’ satisfaction over time and found that participants in the non-variety group were more satisfied than their counterparts. These results illustrate what psychologists call habituation, also known as decreasing marginal utility to economists.

Applying Habituation to Digital Consumption

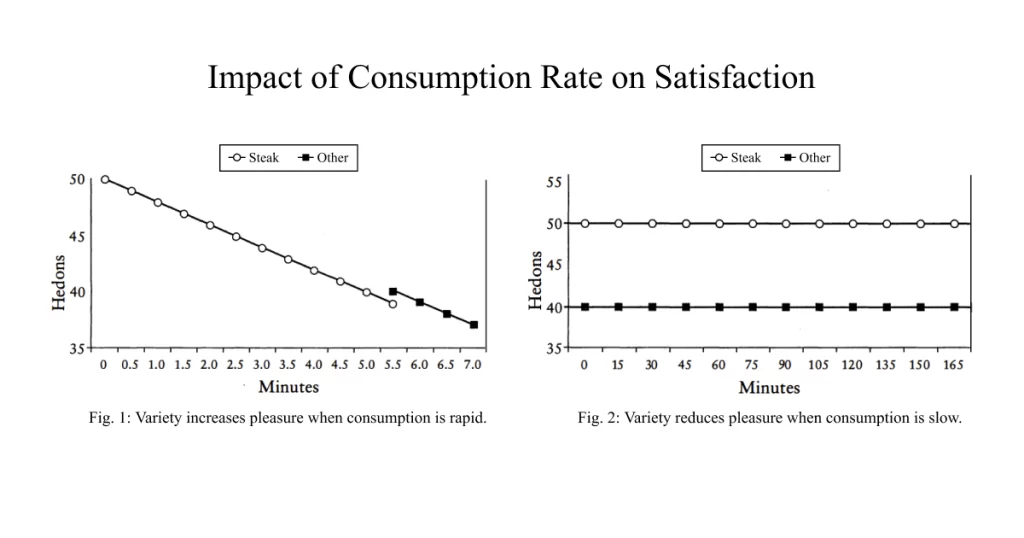

The satisfaction we derive from each experience lessens with repeated exposure. The first chip in a Doritos bag tastes different than the last. That catchy pop song stuck in your head is now unbearable. Variety provides short relief from habituation, but the better response is reduced consumption. If we give ourselves enough time between experiences, our psychological satisfaction returns to a baseline. Think back to the fancy dinner. When your second visit is due, that steak may not taste as delicious as your first, but it will still taste better than anything else on the menu. Our imaginations instinctively visualize twelve steaks side-by-side on a single table, but the more accurate depiction would be twelve steaks on twelve separate tables. As the author puts it, we’re not eating twelve steaks simultaneously; we’re eating twelve steaks sequentially. How does habituation relate to entertainment? When it comes to digital content, our default mode is rapid consumption. We mindlessly consume content at the rate of its production. These businesses thrive on more screen time, costing us our well-being. Variable rewards, infinite scroll, FOMO, and persuasive design keep us glued to screens.

Prioritizing Familiar Experiences

What happens if we say no to novelty? Instead, what if we embraced the things we already love? You already know your favorite TV shows, and you’ve probably rewatched them countless times. Without realizing it, you’re already practicing reduced consumption because you keep going back to the same shows. The same can be said for your video game collection, music library, podcast cycle, and movie marathons. We can double down on our favorite content and ignore the new. Experiment and find a number that works for you: one show, two shows, or three shows. Committing ourselves to familiar experiences will bring us long-term satisfaction and happiness. No more worrying about what next show to watch or drifting aimlessly in menu screens. No more binging content just because it’s there. Our screen time will feel more nourishing, and novel experiences will return to their rightful position as rare occasions. Not only are we relinquishing ourselves from distraction, but we are creating deeper connections with the things we love.